December 17th, 2013

|

|

This head portrait of a breeding plumage Heerman’s Gull was created with the predecessor of the Gitzo 3532 LS carbon fiber tripod, the Mongoose M3.6 head, the 500mm f/4L IS lens (now replaced by the Canon EF 500mm f/4L IS II USM lens), the 2X II TC (now replaced by the Canon 2x EF Extender III (Teleconverter))), and the EOS-1Ds Mark II (now replaced by the Canon EOS-1D X). ISO 400. Evaluative metering +1/3 stop: 1/100 sec. at f/9 in Av mode. Color Temperature: Cloudy.

Central sensor/AI Servo Rear Focus AF as framed active at the moment of exposure. Click here to see the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

Breeding plumage Heerman’s Gulls will be fairly easy subjects on the Short Notice Small Group San Diego IPT. See below for details.

|

What Garbage Can?

Before you read on, do you see the garbage can in the image above?

Watch a good nature photographer. See how long they remain in one spot without moving their tripod. Unless they are staying on one spot doing flight photography they will be moving a lot. At the Venice Rookery it is not uncommon to see photographers who set their tripods down in a good location at 7am and do not move it for 3 or 4 hours. In that time a good photographer will have moved their tripod between 50 and 500 times. Sometimes these moves are of an inch or two, to hide a bright twig behind the subject. At other times they might move their tripod anywhere from 1 foot to 100 yards to get on light angle (have their shadow pointing at the subject), to be in the right spot considering the wind direction or intensity, or as mentioned above, to get a better perspective that will yield a cleaner background.

The image above was created on a San Diego IPT at one of my favorite afternoon spots. In some years the folks who clean the beach create berms of sand about 3 feet high. We toss bread onto the top of the sand ridges for the Heerman’s, Western, and Ring-billed Gulls that frequent the beach there. We had lots of handsome birds lined up on the ridge and folks were easily getting close enough to create head portraits with a telephoto lens and a teleconverter. As you can see above it was late in the day; the light was sweet. And the distant beach in the background was in shade thus the lovely grey background that you see in front of the bird.

Moving left and right I picked off attractive subjects one after another with the old 500 and the 1.4X II TC when I saw a unique opportunity. I switched to the 2X TC, moved well to my right, and created a short series of images before the handsome gull flew off. I quickly got back to the group to share my prize. Reaction was uniform across the board: “Where did you get that beautiful blue in the background? Our backgrounds are nice with that shaded slate grey but yours is amazing. I said, “It’s right there in front of you. Just look.” More of the same: “There’s no blue anywhere!”

Then I pointed about fifty yards to our right at a large, squat blue plastic trash receptacle….

By carefully, and I mean very carefully, positioning my tripod I was able to center the gull’s head against the out-of-focus blue of the hard plastic garbage can. Understand that if my tripod has been placed as little as a half-inch to either side that the image would not have been as strong. Once I explained things to the group we put some more bread on the berm and folks went to work with their newly found blue background.

Here’s the principle: always choose your perspective carefully to create the cleanest, boldest images possible. BTW, I love the American Flag color scheme of today’s image.

|

|

|

Join me in San Diego for three great days of photography and learning. Click on the image to better enjoy a larger version.

|

Pelican Paradise

LaJolla, California is a pelican paradise. At the right time of year, most will be sporting their incredibly beautiful breeding plumage of white and yellow and deep chocolate brown. But it is the olive green and bright red bill pouches that grabs you by the throat and never lets go. One of my LaJolla film images was honored in the BBC Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competitions. Today, I still don’t have enough pelican images. I’d love to make another BBC-worthy photograph on my upcoming trip. I hope that you can join me in the quest. See below for details.

I’ve been away from LaJolla for too long. I visited San Diego for photography (and until 2007, to visit my folks who lived in North

park; my war hero Dad died in 2001) every year for almost three decades. My Mom, now 91 and living in Holbrook, Long Island, NY, lived in San Diego until seven years ago. Whenever I walked into my parent’s home on Pentuckett Avenue the same conversation would take place:

Hazel Louise Morris: What are you gonna do tomorrow?

Arthur Edward Morris: Ma, you know what I am gonna do tomorrow.

HLM: What are you gonna do tomorrow?

AEM: Ma, I’m going to LaJolla bright and early.

HLM: What are you gonna do there?

AEM: Ma, you know what I am gonna do.

HLM: What are you gonna do there?

AEM: Ma, I’m going to photograph those beautiful pelicans.

HLM: Don’t you have enough pelican pictures alreadY?

AEM: No Ma.

Announcing the San Diego Short-Notice Small Group IPT. January 15-17, 3-Full Days: $1049. Meet and Greet after dinner on your own at 7:30pm on Tuesday, January 14, 2014. Limit 6.

We will get to photograph the California race of Brown Pelican in flight, resting, preening, cleaning their bill pouches, and talking to their neighbors by tossing their bills high in the air. The afternoon sessions will feature Marbled Godwits, several gull species, and Wood and Ring-necked Ducks. If we have a cloudy morning we will get to photograph Harbor Seals. You will learn to get the right exposure every time, to see the best situation, to think like a pro, to create sharp, pleasing images, and to understand the joint effects of light and wind on the birds. All in a small group with tons of individual attention.

A $500 non-refundable deposit is required to hold your slot for this IPT. Your balance will be due no later than January 7, 2014. The balance is alo non-refundable. If the trip fills, we will be glad to apply a credit applicable to a future IPT for the full amount less a $100 processing fee. If we do not receive your check for the balance on or before the due date we will try to fill your spot from the waiting list. If your spot is filled, you will lose your deposit. If not, you can secure your spot by paying your balance.

If you are planning to register please shoot me an e-mail.

Then please print, complete, and sign the form that is linked to here and shoot it to us along with your deposit check (made out to “Arthur Morris.”) Though we prefer a check, you can also leave your deposit with a credit card by calling the office at 863-692-0906. If you register by phone, please print, complete and sign the form as noted above and either mail it to us or e-mail the scan.

If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me via e-mail

San Diego Site Guide

Can’t make the IPT? Get yourself a copy of the San Diego Site Guide; it’s the next best thing to being on an IPT. Nearly 30 years of San Diego bird photography secrets revealed in one fell swoop.

Great buy: Used Canon 800mm f/5/6L IS Lens for Sale

Friend and multiple IPT-veteran Monte Brown is offering his lightly used Canon 800mm f/5.6L IS lens in excellent condition for sale for $9,500. Purchase includes the lens case and hood, the 4th Generation Design Low Foot, the original foot, a LensCoat, the original invoice and the original Canon shipping carton. The lens was purchased new from B&H in April 2009 and was recently underwent a pre-sale clean and check by Canon. The buyer pays insured shipping via UPS Ground to US addresses only. The lens will be shipped only after your check clears.

The Canon EF 800mm f/5.6L IS USM Autofocus lens sells new for $13,223.00 so you will save a bundle on a great lens. No need to ever use a 2X…

If interested you can contact Monte by phone at 1-765-744-1421 or via e-mail.

Last Year’s Grand Prize winning image by Lou Coetzer

Time is Running Out!

BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition

The December 31, 2013 closing deadline is fast approaching.

Learn more and enter the BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition here. Twenty-five great prizes including the $1000 Grand Prize and intense competition. Bring your best.

Support the BAA Blog. Support the BAA Bulletins: Shop B&H here!

We want and need to keep providing you with the latest free information, photography and Photoshop lessons, and all manner of related information. Show your appreciation by making your purchases immediately after clicking on any of our B&H or Amazon Affiliate links in this blog post. Remember, B&H ain’t just photography!

Amazon

Everyone buys something from Amazon, be it a big lens or deodorant. Support the blog by starting your search by clicking on the logo-link below. No purchase is too small to be appreciated; they all add up. Why make it a habit? Because I make it a habit of bringing you new images and information on an almost daily basis.

Typos

In all blog posts and Bulletins feel free to e-mail or leave a comment regarding any typos, wrong words, misspellings, omissions, or grammatical errors. Just be right. 🙂

IPT Info

Many of our great trips are filling up. You will learn more about how to make great images on a BAA IPT than anywhere else on the planet. Click here to learn about the just-announced 2014 Bosque IPTs. And click here for the schedule and additional info.

December 16th, 2013

You Should Be So Lucky

On the first morning of the first day of the 2006 “President’s Week Southwest Florida IPT this bird flew in and landed nearby on a foggy bright morning. I helped the group get into position. A few of us got to make a frame or two. And then the drop-dead gorgeous bird flew off and disappeared over the condos bound for who knows where?

Someone said, “We scared it away.” Nope I said, the birds here are all tame; but Reddish Egrets can be finicky.

Same time, same place, one day later. The same bird flew in at about 7:45 am on a clear morning, landed right in front of the entire group, and posed for about one solid hour. I urged folks to add and subtract their TCs. to use different lenses, to do some human zoomin’, and to change their perspective. The bright pink and ultramarine soft parts’ colors of white morph Reddish Egrets last for only a few days. And they only occur when the birds are actively involved with breeding. You can see the best of the several hundred images that I created of this most beautiful bird in The Art of Bird Photography II. ABP II, 916 pages, 900+ images, makes a great stocking stuffer.

If you live long enough and get lucky, you will get to photograph a bird just like this at least once before they nail the box shut.

|

|

This Snowy Egret was photographed in pre-dawn light at Little Estero Lagoon with the hand held Canon EF 70-200mm f/2.8L IS II USM lens (at 100mm) and the EOS-50D (now replaced for me by the Canon EOS 5D Mark III Digital camera body ISO 800. Evaluative metering +1 stop as framed: 1/500 sec. at f/5.6 in Av mode.

One-shot AF and re-compose. Talk about the old days–no rear focus…. Be sure to click on the image to enjoy a larger version.

|

Bird Photography Hotspot: Little Estero Lagoon, Fort Myers Beach, FL

The first time that I tried to find Little Estero Lagoon I had no luck at all. I drove to Fort Myers Beach in a ton of traffic and when I arrived all that I saw were hundreds of young kids walking around in bathing suits with a beer in one hand and a frisbee in the other. Those with a free hand were hauling coolers with more brews. I paid way, way too much to park, walked down to the beach, and saw a very few Laughing Gulls and about 10,000 folks getting sunburned.

Well more than two decades later, I know the ropes at Little Estero as well as anyone. Every year folks tell me, “There’s not much at Estero.” I go the next day and fill every flash card that I have. It’s all a matter of knowing where to be when. It is not uncommon to photograph all of the following species in a single day: Great Egret, Snowy Egret, Tricolored Heron, Reddish Egret (both color morphs), Great Blue Heron, Little Blue Heron, Ring-billed Gull, Laughing Gull, Royal Tern, Forster’s Tern, Black-bellied Plover,Ruddy Turnstone, Semipalmated Plover, Wilson’s Plover, Piping Plover, American Oystercatcher, Double-crested Cormorant, Mottled Duck, Brown Pelican, and Osprey. Wood Stork, Sandwich Tern, White Pelican, Black Skimmer, Herring Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Long-billed Curlew, Snowy Plover, Western Sandpiper, Dunlin, Short-billed Dowitcher, Red Knot, Bald Eagle, and Roseate Spoonbill are all possible. And the best news is that nearly all of the birds are silly tame.

Being in the right spot at the right time while photographing a huge feeding spree in gorgeous light is for me the thrill of Little Estero.

Your Favorite?

Which of the two images above do you like best? Be sure to let us know why you made your choice.

Southwest Florida Site Guide

My Southwest Florida Site Guide includes detailed instructions for photographing at the great spots within an hour or two of Fort Myers, Florida. Included are Ding Darling NWR then and now, Blind Pass Beach, the Sanibel Fishing Pier, the East Gulf Beaches–great for Snowy Plover, Little Estero Lagoon, the Sanibel Causeway, Venice Rookery, my secret White Pelican spot–head shots with a 300mm lens plus flight and action, and the two best Burrowing Owl sites on Cape Coral. Learn more or purchase here.

|

|

Join us to learn the ins and outs of Little Estero Lagoon.

|

Little Estero Lagoon IPT: 2 full days–Sat/Sun: JAN 25-26 (Limit 14/Openings 12): $799. Introductory slide program: 7pm, FRI, JAN 24, 2014

Join Denise Ippolito and Arthur Morris for four great photography sessions at one of the top bird photography hotspots in North America. Morning sessions: 6:15am to 10:30am. Afternoon sessions: 3:00pm till 5:45pm. Lunch included. Informal image review and Photoshop sessions after lunch. Call 863-292-0906 to registger; payment if full is now due so call with your credit card in hand. Please e-mail with any questions.

Monday: Jan 27: Optional Estero Add-on/morning only (Limit 14/Openings 12): $249

Adding the last morning as above is an option.

What you will learn:

When to be where and where to be when at Little Estero Lagoon to maximize the photographic opportunities.

Autofocus basics and correct camera and gear set-up.

How to get the right exposure with digital every time.

How and why to expose to the right.

How to create pre-dawn silhouettes.

How to design pleasing images.

How to find the best perspective.

How to make strong images in cluttered situations.

How to photography birds in flight.

In-the-Field creative techniques.

Do consider joining us for the all or part of the South Florida Composite IPT:

2014 South Florida Composite IPT: 6 1/2 days of photography spread over 9 days of learning, hanging out, and travel: $2644. (Limit 14/Openings: 12

Click here for complete details or to register. Please e-mail with any questions or leave a comment below.

Last Year’s Grand Prize winning image by Lou Coetzer

Time is Running Out!

BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition

The December 31, 2013 closing deadline is fast approaching.

Learn more and enter the BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition here. Twenty-five great prizes including the $1000 Grand Prize and intense competition. Bring your best.

Support the BAA Blog. Support the BAA Bulletins: Shop B&H here!

We want and need to keep providing you with the latest free information, photography and Photoshop lessons, and all manner of related information. Show your appreciation by making your purchases immediately after clicking on any of our B&H or Amazon Affiliate links in this blog post. Remember, B&H ain’t just photography!

Amazon

Everyone buys something from Amazon, be it a big lens or deodorant. Support the blog by starting your search by clicking on the logo-link below. No purchase is too small to be appreciated; they all add up. Why make it a habit? Because I make it a habit of bringing you new images and information on an almost daily basis.

Typos

In all blog posts and Bulletins feel free to e-mail or leave a comment regarding any typos, wrong words, misspellings, omissions, or grammatical errors. Just be right. 🙂

IPT Info

Many of our great trips are filling up. You will learn more about how to make great images on a BAA IPT than anywhere else on the planet. Click here for the schedule and additional info.

December 15th, 2013

Gear Bag Discussion for a Big Trip

Denise Ippolito and I are taking 7 clients on a long-sold-out Japan in Winter IPT leaving the US on February 10th. Paul McKenzie who helped organize the trip–he lives in Hong Kong–is co-leading. There have been lots of questions about what lenses to bring. Below I share a few of the e-mails discussing just that subject. As you read the e-mails, do consider the images presented here and how they relate to the e-mails and to you.

From My First Gear e-Mail to the Group

Hi Gang,

I am in a quandary. The first (and last) time that I went to Japan I brought the 300 f/2.8 L IS II and the 800 for big glass. I did use the 800 a bit for head portraits of the eagles off the tripod–yes, on the boat and a lot for photographing the cranes in flight, often with the 1.4X TC. That said I made a ton of great images with the 300/1.4X TC combo and with the 70-200 II.

I no longer own the 800 having replaced it with the 600 f/4L IS II. And I also own the 200-400 with internal TC…

I am trying to decide whether to bring the 200-400 and perhaps a 300 II–the latter is lighter and much easier to hand hold and leave the 600 II at home…. The 2-4 with both TC gets me to 784mm. But the 600 with the 2X TC gets me to 1200, a huge advantage…. I expect that Paul will often have a shorter rather than a longer lens in his hands than me as he loves doing the wide environmental stuff…. I will be also bringing the 24-105 and leaving the fish eye at home….

So my big decision is whether to bring the 600 II or the 200-400 as my big lens. I am leaning towards the 600 II. If I do that I will almost surely buy a new 300 II and bring that so that I have something lighter for flight. The 2-4 would be great but it is heavier and it is nearly impossible to bring the 600 II, the 2-4, and the 300 II and all the rest. Heck, the 600II and the 300 II is load enough…

An option that I did not mention was to do the whole trip without a big super-telephoto, that is, to go only with the 300f/2.8L IS and both teleconverters…. For those considering bring a 200-400 the edge of course goes to the Canon version with the internal TC.

ps: bring lots of layers as the eagle boat might be brutally cold. I think that we had -5F one morning…. But there is a warm cabin.

pps: some might opt to do an afternoon trip at additional expense or possibly to do only one trip in the morning and one in the afternoon. We need six to get an afternoon boat but we could always recruit some other photographers….

|

|

This breeding plumage Brown Pelican image was created at LaJolla, CA in January 2006 with the predecessor of the Gitzo 3532 LS carbon fiber tripod, the Mongoose M3.6 head, the 600mm f/4L IS lens) now replaced by the Canon EF 600mm f/4L IS II USM lens) and the EOS-1D Mark II (now replaced by the Canon EOS-1D X). ISO 400. Evaluative metering at zero in Av mode. Color temperature: Cloudy.

Central sensor/Rear Focus AF on the bird’s eye and re-compose. Click here to see the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

Note that as recently as 2011 I was working most often in Av mode rather than Manual mode…

|

Early Morning Thoughts…

Hi Again All, Here I will share the thoughts that I was having as I awoke in a somewhat dream-like state this morning….

I have always been a long lens guy. I see the world in small rectangular frames as if I were always looking through a long telephoto lens. With a teleconverter. I love 3/4 frame images of whole birds and I love tight head portraits with clean backgrounds. Please remember that that is me. That is my style. I believe that Denise is much the same. I know that Paul tends to work much wider than I do using shorter focal length lenses so as to include lots of beautiful habitat. That said, I think that Paul had his the 600 when I last saw him in Japan. I might be wrong though….

If you brought only a 70-200 with TCs or an 80-400 or 100-400 without TCs or one of the Sigma 50-500s you will have countless opportunities to create great images on the Japan in Winter trip. Will you sometimes be wishing that you had a longer focal length? Of course. I often wish the same when standing behind my tripod-mounted 600 II with the 2X III attached. But do understand that intermediate focal length lenses above often have a huge advantage over long glass when it comes to photographing birds in flight and in action. I am often dead in the water with the super-long focal lengths that I otherwise enjoy working with….

So please temper my enthusiasm for long glass by remembering that that is me, that that is my style. Please consider the type of images that you like to make before packing your gear bag.

I’d love to hear from Paul and from Denise on their gear bag recommendations.

Denise Wrote:

Hello everyone. I will be bringing my Canon 5D Mark III, Canon 1D Mark IV, Canon 300mm f/2,8 Version II lens, Canon 100-400mm lens, 1.4 III teleconverter, 2X III teleconverter, 24-105mm lens and my 15mm fisheye (it weighs next-to-nothing). And maybe a 16-35mm and/or a 24mm tiltshift. I have decided to leave the 600mm II at home and rely on the 300mm with teleconverters as my big glass. See you all soon! Denise

To Which I Responded:

Wow! She’s going light. Thanks for chiming in Lady D. The 300 f/2.8L IS lens is killer and I will almost surely be bringing one. a

My Reply to Srdjan Mitrovic’s e-Mail

AM: Hi Srdjan, re:

SM: Art, thanks for the recommendations.

AM: YAW.

SM: I can add a 1.4x TCE to the new 80-400 . It becomes f/8 and but am uncertain about the quality.

AM: Though I have no personal experience with that lens and a TC I generally recommend against such combos as the speed of initial AF acquisition is slowed considerably. The same applies to the Canon 100-400mm.

SM: We have also 1.7x TCE and the 2x TCE that we could use on 200-400.

AM: Again, though I have no personal experience with that lens and a TC, I must say that recently I have been hearing many negative comments about the 1.7x TCE, most recently on the Bosque IPT where several folks stated that they owned the 1.7x TCE but have quit using it because of concerns about sharpness. And the Nikon 2x TCEs have been trashed by everyone I know who uses Nikon. Except for Todd Gustafson who regularly uses both the 1.7x TCE and the 2x TCE with his 600 f/4 Nikkor lens…. Everyone that I know is happy with the image quality from the 200-400 with the 1.4x TCE.

SM: If I understand correctly we should have at least 600mm full frame lens reach, correct?

AM: I am not so sure about that… See my comments above.

SM: D800s are 36 MP full frame bodies.

AM: With that file size using a shorter lens and cropping will produce some superb image files even with a large crop. With the 200-400 and the 1.4X TCE and the new 80-400 for hand held flight photography and your 36mp you should be more than fine….

Please let me know if you have any additional questions.

later and love, artie

ps: for more on Nikon lenses and TCEs see Big Lens Choices for Canon and Nikon–As I See Them….

The Great Group

We really have put together a great group of truly Happy Campers. Alan and Pat Lillich are both great friends and multiple IPT veterans. Both are accomplished photographers and Pat is a talented sculptress as well. I first met Zorica Kovacevic and Srdjan Mitrovic at Tierra del Fuego National Park where we hung out together and got more than a few great images of some Magellanic Woodpeckers. We then spent three great weeks together on a Cheesemans Antarctica/South Georgia/Falklands cruise. The always-smiling Scotsman (one “t” is correct) Malcolm MacKenzie is another mutliple IPT veteran. He lives in Connecticut. Rounding out the crew are newcomers Lex and Debbie Franks who will be traveling from Australia for their first Instructional Photo-Tour. We all look forward to meeting our soon-to-be new friends from Down Under.

Your Favorite?

Which of the three images above do you feel is the strongest? Be sure to let us know why.

|

|

|

Join me in San Diego for three great days of photography and learning. Click on the image to better enjoy a larger version.

|

Announcing the San Diego Short-Notice Small Group IPT. January 15-17, 3-Full Days: $1049. Meet and Greet after dinner on your own at 7:30pm on Tuesday, January 14, 2014. Limit 6.

We will get to photograph the California race of Brown Pelican in flight, resting, preening, cleaning their bill pouches, and talking to their neighbors by tossing their bills high in the air. The afternoon sessions will feature Marbled Godwits, several gull species, and Wood and Ring-necked Ducks. If we have a cloudy morning we will get to photograph Harbor Seals. You will learn to get the right exposure every time, to see the best situation, to think like a pro, to create sharp, pleasing images, and to understand the joint effects of light and wind on the birds. All in a small group with tons of individual attention.

A $500 non-refundable deposit is required to hold your slot for this IPT. Your balance will be due no later than January 7, 2014. The balance is alo non-refundable. If the trip fills, we will be glad to apply a credit applicable to a future IPT for the full amount less a $100 processing fee. If we do not receive your check for the balance on or before the due date we will try to fill your spot from the waiting list. If your spot is filled, you will lose your deposit. If not, you can secure your spot by paying your balance.

If you are planning to register please shoot me an e-mail.

Then please print, complete, and sign the form that is linked to here and shoot it to us along with your deposit check (made out to “Arthur Morris.”) Though we prefer a check, you can also leave your deposit with a credit card by calling the office at 863-692-0906. If you register by phone, please print, complete and sign the form as noted above and either mail it to us or e-mail the scan.

If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me via e-mail

San Diego Site Guide

Can’t make the IPT? Get yourself a copy of the San Diego Site Guide; it’s the next best thing to being on an IPT. Nearly 30 years of San Diego bird photography revealed in one fell swoop.

Great buy: Used Canon 800mm f/5/6L IS Lens for Sale

Friend and multiple IPT-veteran Monte Brown is offering his lightly used Canon 800mm f/5.6L IS lens in excellent condition for sale for $9,500. Purchase includes the lens case and hood, the 4th Generation Design Low Foot, the original foot, a LensCoat, the original invoice and the original Canon shipping carton. The lens was purchased new from B&H in April 2009 and was recently underwent a pre-sale clean and check by Canon. The buyer pays insured shipping via UPS Ground to US addresses only. The lens will be shipped only after your check clears.

The Canon EF 800mm f/5.6L IS USM Autofocus lens sells new for $13,223.00 so you will save a bundle on a great lens. No need to ever use a 2X…

If interested you can contact Monte by phone at 1-765-744-1421 or via e-mail.

Last Year’s Grand Prize winning image by Lou Coetzer

Time is Running Out!

BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition

The December 31, 2013 closing deadline is fast approaching.

Learn more and enter the BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition here. Twenty-five great prizes including the $1000 Grand Prize and intense competition. Bring your best.

Support the BAA Blog. Support the BAA Bulletins: Shop B&H here!

We want and need to keep providing you with the latest free information, photography and Photoshop lessons, and all manner of related information. Show your appreciation by making your purchases immediately after clicking on any of our B&H or Amazon Affiliate links in this blog post. Remember, B&H ain’t just photography!

Amazon

Everyone buys something from Amazon, be it a big lens or deodorant. Support the blog by starting your search by clicking on the logo-link below. No purchase is too small to be appreciated; they all add up. Why make it a habit? Because I make it a habit of bringing you new images and information on an almost daily basis.

Typos

In all blog posts and Bulletins feel free to e-mail or leave a comment regarding any typos, wrong words, misspellings, omissions, or grammatical errors. Just be right. 🙂

IPT Info

Many of our great trips are filling up. You will learn more about how to make great images on a BAA IPT than anywhere else on the planet. Click here to learn about the just-announced 2014 Bosque IPTs. And click here for the schedule and additional info.

December 14th, 2013

|

|

This Brown Pelican image was was created at LaJolla, CA with the Gitzo 3532 LS carbon fiber tripod, the Mongoose M3.6 head, the Canon EF 800mm f/5.6L IS USM Autofocus lens, the Canon 1.4x EF Extender III (Teleconverter), and the EOS-1D Mark IV now replaced by the Canon EOS-1D X. ISO 500. Evaluative metering +1 stop: 1/30 sec. at f/20 in Av mode.

Central sensor/Rear Focus AF on the base of the bill less than one half inch in front of the eyes and re-compose. Click here to see the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

The great 4-stop IS system of the 800 allowed me to make a sharp image at 1/30 at 1120mm with an effective magnification of slightly more than 29X! There is a great used 800 for sale below. Though I love my 600II there are times when I miss the 800….

|

Long Lens Depth-of Field Lessons from LaJolla, CA

Lesson I: Depth-of-Field with Long Lenses at Close Range is Miniscule

It is a popular misconception that depth-of-field is always 33.3% in front of point of focus and 66% behind the point of focus. That is true with short lenses like the 24-105 and is an important principle for landscape photographers. But with telephoto lenses depth-of-field is pretty much right on the button at 50/50. That is whatever depth-of-field you have will be spread out equally with 50% in front of point of focus and 50% behind. Not buying that? Want to learn a lot more about d-o-f? As I have suggested before you can learn a ton by visiting DOFMaster by clicking here.

A quick visit with regards to the image above show that the d-o-f is indeed 50/50 with .36 inches in front of and .36 inches beyond the point of focus being in relatively sharp focus. That means that the total d-o-f is less than three-quarters of a single inch. That at f/20! As I have been writing, teaching, and preaching, depth-of-field with long lenses when you are working near the lens’s minimum focusing distance is normally measured in fractions of a single inch. For the image above had I been working wide open at f/8 the total d-o-f field would have been slightly more than one-third of one inch…

Lesson II: Long Lens D-o-F Strategy

To maximize d-o-f, consider the 50-50 principle. For the image above I knew from experience that d-o-f would only be about an inch or less even at f/20 so I focused on the base of the bill less than a half-inch in front of the plane of the eyes. Doing that allowed me render the base of the bill and the eyes to be in relatively sharp focus. Though the d-o-f was so shallow, I was at least able to use it fairly effectively by knowing exactly where to focus.

If you have any d-o-f questions, please leave a comment and ask away.

|

|

|

Join me in San Diego for three great days of photography and learning. Click on the image to better enjoy a larger version.

|

Pelican Paradise

LaJolla, California is a pelican paradise. At the right time of year, most will be sporting their incredibly beautiful breeding plumage of white and yellow and deep chocolate brown. But it is the olive green and bright red bill pouches that grabs you by the throat and never lets go. One of my LaJolla film images was honored in the BBC Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competitions. Today, I still don’t have enough pelican images. I’d love to make another BBC-worthy photograph on my upcoming trip. I hope that you can join me in the quest. See below for details.

I’ve been away from LaJolla for too long. I visited San Diego for photography (and until 2007, to visit my folks who lived in North

park; my war hero Dad died in 2001) every year for almost three decades. My Mom, now 91 and living in Holbrook, Long Island, NY, lived in San Diego until seven years ago. Whenever I walked into my parent’s home on Pentuckett Avenue the same conversation would take place:

Hazel Louise Morris: What are you gonna do tomorrow?

Arthur Edward Morris: Ma, you know what I am gonna do tomorrow.

HLM: What are you gonna do tomorrow?

AEM: Ma, I’m going to LaJolla bright and early.

HLM: What are you gonna do there?

AEM: Ma, you know what I am gonna do.

HLM: What are you gonna do there?

AEM: Ma, I’m going to photograph those beautiful pelicans.

HLM: Don’t you have enough pelican pictures already?

AEM: No Ma.

Announcing the San Diego Short-Notice Small Group IPT. January 15-17, 3-Full Days: $1049. Meet and Greet after dinner on your own at 7:30pm on Tuesday, January 14, 2014. Limit 6/Openings: 1.

We will get to photograph the California race of Brown Pelican in flight, resting, preening, cleaning their bill pouches, and talking to their neighbors by tossing their bills high in the air. The afternoon sessions will feature Marbled Godwits, several gull species, and Wood and Ring-necked Ducks. If we have a cloudy morning we will get to photograph Harbor Seals. You will learn to get the right exposure every time, to see the best situation, to think like a pro, to create sharp, pleasing images, and to understand the joint effects of light and wind on the birds. All in a small group with tons of individual attention.

A $500 non-refundable deposit is required to hold your slot for this IPT. Your balance will be due no later than January 7, 2014. The balance is alo non-refundable. If the trip fills, we will be glad to apply a credit applicable to a future IPT for the full amount less a $100 processing fee. If we do not receive your check for the balance on or before the due date we will try to fill your spot from the waiting list. If your spot is filled, you will lose your deposit. If not, you can secure your spot by paying your balance.

If you are planning to register please shoot me an e-mail.

Then please print, complete, and sign the form that is linked to here and shoot it to us along with your deposit check (made out to “Arthur Morris.”) Though we prefer a check, you can also leave your deposit with a credit card by calling the office at 863-692-0906. If you register by phone, please print, complete and sign the form as noted above and either mail it to us or e-mail the scan.

If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me via e-mail

San Diego Site Guide

Can’t make the IPT? Get yourself a copy of the San Diego Site Guide; it’s the next best thing to being on an IPT. Nearly 30 years of San Diego bird photography revealed in one fell swoop.

Great buy: Used Canon 800mm f/5/6L IS Lens for Sale

Friend and multiple IPT-veteran Monte Brown is offering his lightly used Canon 800mm f/5.6L IS lens in excellent condition for sale for $9,500. Purchase includes the lens case and hood, the 4th Generation Design Low Foot, the original foot, a LensCoat, the original invoice and the original Canon shipping carton. The lens was purchased new from B&H in April 2009 and was recently underwent a pre-sale clean and check by Canon. The buyer pays insured shipping via UPS Ground to US addresses only. The lens will be shipped only after your check clears.

The Canon EF 800mm f/5.6L IS USM Autofocus lens sells new for $13,223.00 so you will save a bundle on a great lens. No need to ever use a 2X…

If interested you can contact Monte by phone at 1-765-744-1421 or via e-mail.

Last Year’s Grand Prize winning image by Lou Coetzer

Time is Running Out!

BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition

The December 31, 2013 closing deadline is fast approaching.

Learn more and enter the BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition here. Twenty-five great prizes including the $1000 Grand Prize and intense competition. Bring your best.

Support the BAA Blog. Support the BAA Bulletins: Shop B&H here!

We want and need to keep providing you with the latest free information, photography and Photoshop lessons, and all manner of related information. Show your appreciation by making your purchases immediately after clicking on any of our B&H or Amazon Affiliate links in this blog post. Remember, B&H ain’t just photography!

Amazon

Everyone buys something from Amazon, be it a big lens or deodorant. Support the blog by starting your search by clicking on the logo-link below. No purchase is too small to be appreciated; they all add up. Why make it a habit? Because I make it a habit of bringing you new images and information on an almost daily basis.

Typos

In all blog posts and Bulletins feel free to e-mail or leave a comment regarding any typos, wrong words, misspellings, omissions, or grammatical errors. Just be right. 🙂

IPT Info

Many of our great trips are filling up. You will learn more about how to make great images on a BAA IPT than anywhere else on the planet. Click here to learn about the just-announced 2014 Bosque IPTs. And click here for the schedule and additional info.

December 13th, 2013

Mornings and Afternoons at Bosque

In general, mornings are usually more productive at Bosque (except for the last half hour of light at the crane pools on the right afternoons). And on cloudy days, mornings are almost always far more productive than afternoons.

|

|

|

This image was created with the the Canon EF 200-400mm f/4L IS USM lens with Internal 1.4x Extender (with the internal TC in place hand held at 280mm) and the Canon EOS-1D X. ISO 1600. Evaluative metering +1 2/3 stops as framed in Av Mode: 1/30 sec. at f/5.6. Color temperature 7500 (should have been 10,000 as the RAW file was BLUE).

Central sensor/AI Servo/Surround–Rear Focus AF on the tree in the middle and recompose. Click here to see the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

|

Follow Your Nose…

On the rare cloudy, dreary afternoon the best strategy is to go past the pay booth and flip a coin. Heads, make a right turn and check out the Marsh Loop. Tails go straight up Bosque Road (In the Bosque Site Guide I call it the H Road for obvious reasons). On November 23, the coin came up tails. I was glad as there had been some good concentrations of ducks about 2/3 of the way to the left turn on the Farm Loop. Most of us were messing around with the dispersing ducks, not doing much. A few folks walk a hundred yards up the road to the pool on the right near the intersection. Close to a decade ago this was a good location with lots of ducks and the occasional Neotropic Cormorant. Lately it had been not so good. I forget which member of Denise’s group came back to get us, heck, it might have been Denise, but IAC we were told that there were big groups of blackbirds perching on the dead bushes in the pool and flying around. So we went. The image above was one of the first that I made.

|

|

|

This image was also created with the Canon EF 200-400mm f/4L IS USM lens with Internal 1.4x Extender (with the internal TC in place hand held at 280mm) and the Canon EOS-1D X. ISO 1600. Evaluative metering +1 2/3 stops as framed in Av Mode: 1/30 sec. at f/5.6. Color temperature 7500 (should have been 10,000).

Central sensor/AI Servo/Surround–Rear Focus AF on the tree in the middle and recompose. Click here to see the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

|

And Then the Birds Took Off

And then the birds took off so I pushed the button while panning with the flock.

A Guide to Pleasing Blurs

Pleasing blurs are not out-of-focus mistakes. They are well thought out, skillfully executed, accurately focused creations. If you would like to learn to create such images, get yourself a copy of “A Guide to Pleasing Blurs” by Denise Ipplito and yours truly.

|

|

|

This image was also created with the Canon EF 200-400mm f/4L IS USM lens with Internal 1.4x Extender (hand held at 371mm) and the Canon EOS-1D X. ISO 320. Evaluative metering +1 1/3 stops as framed in Av Mode: 1/10 sec. at f/9. Color temperature 7500.

One sensor below the central sensor/AI Servo/Surround–Rear Focus AF as framed active at the moment of exposure. Click here to see the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

|

Follow Your Nose Part II…

After the mass of birds took off they flew north and west so I said to the group, “Let’s go!” We walked west along the H Road past the spot where we had started so that we had a clear view of the Main Impoundment to the north. The flock swirled and turned and veered. I framed and fired off about 60 images over a ten minute period until the action quit and we headed back to Socorro for dinner.

In the image above I love that the flock had split in two with each segment flying in a different direction.

Image Questions

In the second image, why was it a mistake to have the internal TC in place?

In the second image, considering that I was hand holding, what factors helped me to create a relatively sharp image at only 1/30 sec.?

Which of the images above is your favorite? Why? I have two clear favorites and will share them with you at some point.

|

|

|

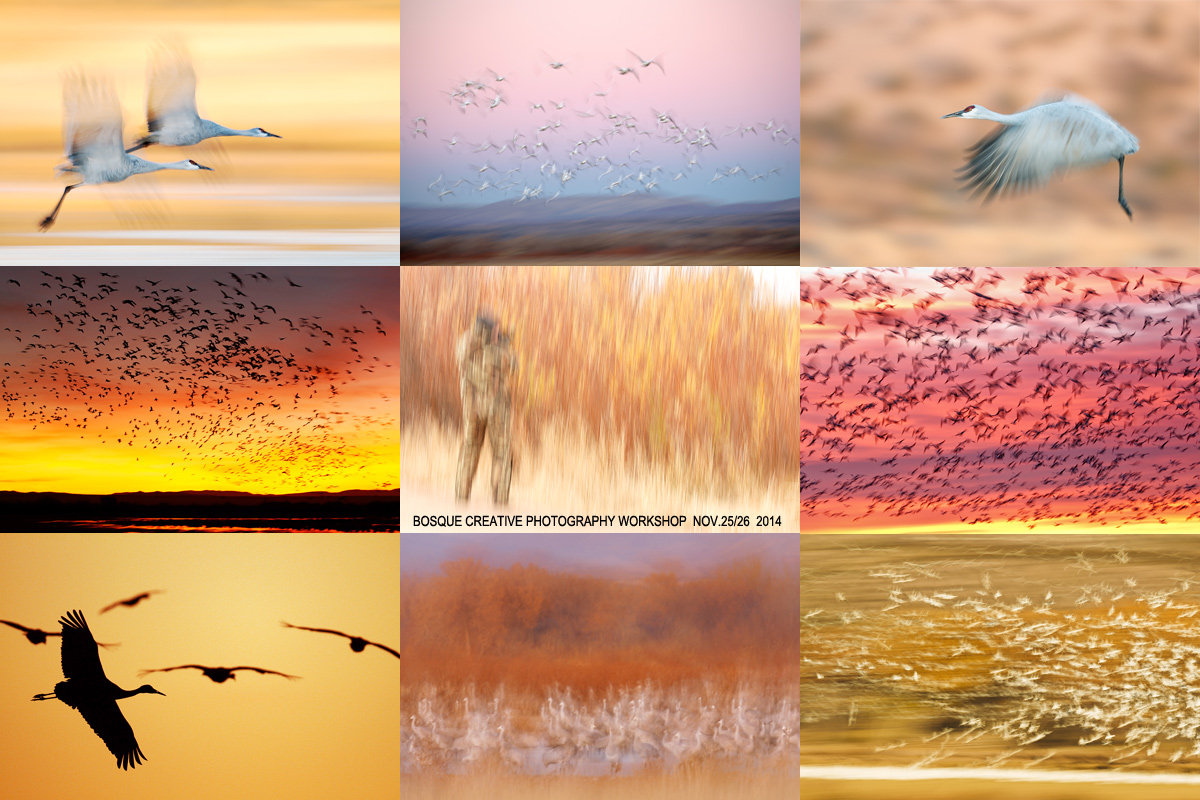

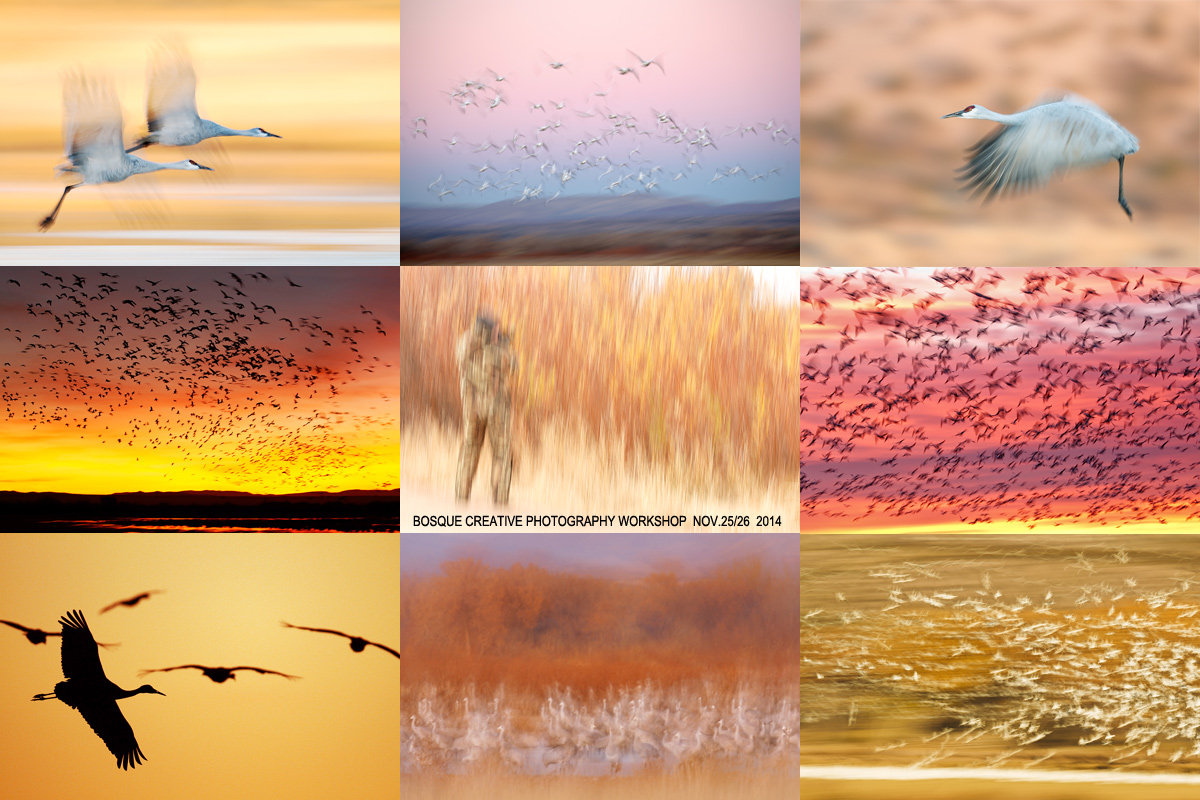

Join Denise Ippolito and me for four great days of photography and learning at one of our soul places. Please click on the card to enjoy a larger version.

|

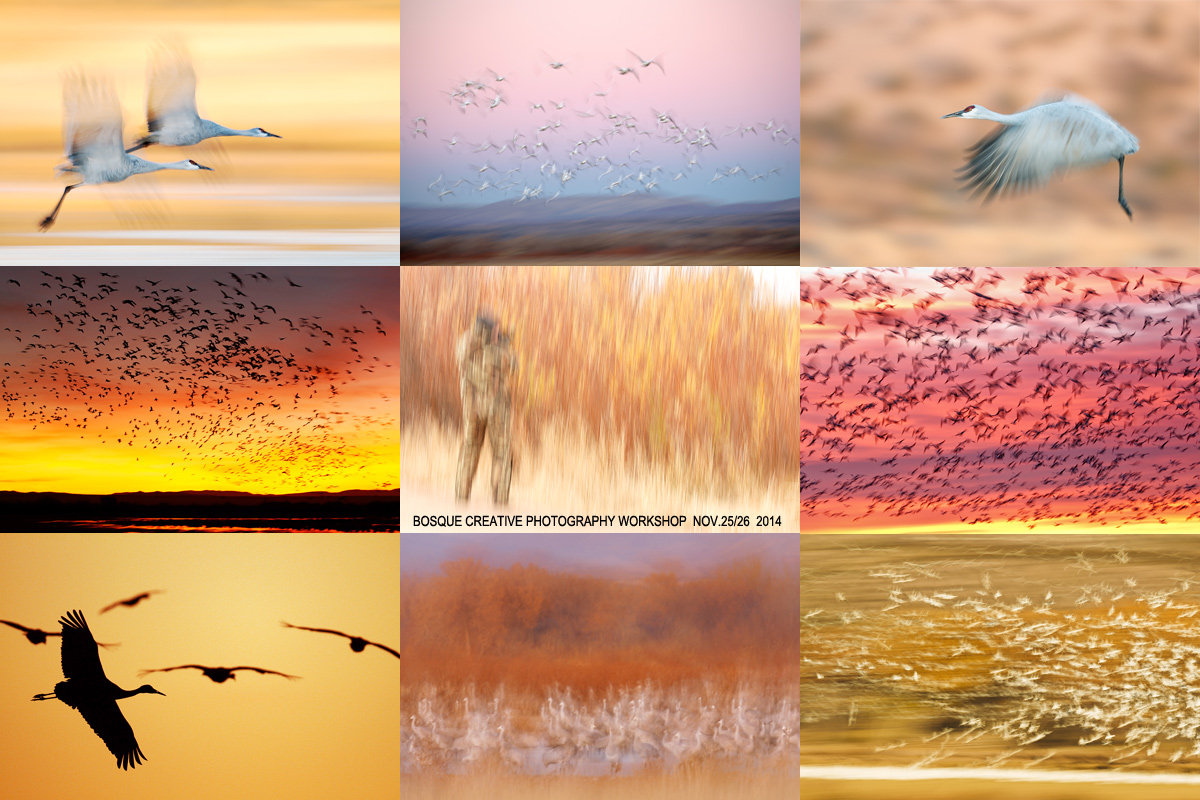

Bosque del Apache 2014 BIRDS AS ART/A Creative Adventure Instructional Photo-Tour (IPT). NOV 29-DEC 3, 2014. Totaling 4 FULL-DAYS: $1449. Leaders: Arthur Morris and Denise Ippolito. Introductory Slide program: 7:00pm on Sunday 11/29.

|

|

|

Join Denise Ippolito and me for two great days of photography, fun, and learning at one of our soul places. We will surely be taking you out of the box on this workshop. Please click on the card to enjoy a larger version.

|

Bosque del Apache 2014 A Creative Adventure/BIRDS AS ART “Creative Photography Instructional Photo-Tour.” (IPT). NOV 24-25, 2014. 2-FULL DAYS: $729. Leaders: Denise Ippolito & Arthur Morris. Introductory Slide program: 7:00pm on Sunday 11/23.

Denise and I hope that you can join us. Click here for complete details.

Delkin Devices

As regular readers know, I keep a Delkin 64gb e-Film Pro 700X flash card in all three of my cameras. I use and depend on them 300 days a year. (Yeah, I know: life is tough. 🙂 You can learn about all the Delkin products that we carry by clicking here. For those of you who prefer SD cards–they are too small for me, we would be glad to have your order drop-shipped for you. Please Jim and let him know what you need.

Delkin has been a long time BAA sponsor. They have been generous supporters of the BAA International Bird Photography Competitions since the get-go. In addition to flash cards and a line of great card readers, Delkin carries an interesting line of products. Click on some of the links below and you just might be able to take care of some of your holiday gift shopping in short order and save some bucks while you are at it.

GoPro Gift Guide + $30 Instant Savings Inside

|

Give a Little Cheer to the GoPro Fan in Your Life.

|

|

Instant savings on the Fat Gecko Kaboom is valid 12/13/13 through 12/31/13 at 11:59 PM PST while supplies last. Limited quantities available. Bargain Basement orders must be placed through delkinbargains.com and cannot be combined with regular Delkin.com orders. Questions? Contact us toll free during normal business hours at (800) 637-8087.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

December 12th, 2013

|

|

|

Join Denise Ippolito and me for four great days of photography and learning at one of our soul places. Please click on the card to enjoy a larger version.

|

Bosque del Apache 2014 BIRDS AS ART/A Creative Adventure Instructional Photo-Tour (IPT). NOV 29-DEC 3, 2014. Totaling 4 FULL-DAYS: $1449. Leaders: Arthur Morris and Denise Ippolito. Introductory Slide program: 7:00pm on Sunday 11/29.

Tens of thousand of Snow Geese, 10,000 Sandhill Cranes, ducks, amazing sunrises, sunsets, and blast-offs. Live, eat, and breathe photography with two of the world’s premier photographic educators at one of their very favorite photography locations on the planet. Top-notch in-the-field and Photoshop instruction. This will make 21 consecutive Novembers at Bosque for artie. This will be denise’s 6th workshop at the refuge. Nobody knows the place better than artie does. Join us to learn to think like a pro, to recognize situations and to anticipate them based on the weather, especially the sky conditions, the light, and the wind direction. Every time we make a move we will let you know why. When you head home being able to apply what you’ve learned on your home turf will prove to be invaluable.

This workshop includes 4 afternoon (11/29 through 12/2), 4 morning (11/30 to 12/3) photography sessions, an inspirational introductory slide program after dinner on your own on Saturday, 11/29, all lunches, and after-lunch digital workflow, Photoshop, and image critiquing sessions.

There is never a strict itinerary on a Bosque IPT as each day is tailored to the local conditions at the time and to the weather. We are totally flexible in order to maximize both the photographic and learning opportunities. We are up early each day leaving the hotel by 5:30 am to be in position for sunrise. We usually photograph until about 10:30am. Then it is back to Socorro for lunch and then a classroom session with the group most days. We head back to the refuge at about 3:30pm each day and photograph until sunset. We will be photographing lots of Snow Geese and lots of Sandhill Cranes with the emphasis on expanding both your technical skills and your creativity.

A $449 non-refundable deposit is required to hold your slot for this IPT. Your balance, payable only by check, will be due on 7/25/2014. If the trip fills, we will be glad to apply a credit applicable to a future IPT for the full amount less a $100 processing fee. If we do not receive your check for the balance on or before the due date we will try to fill your spot from the waiting list. If your spot is filled, you will lose your deposit. If not, you can secure your spot by paying your balance.

Please print, complete, and sign the form that is linked to here and shoot it to us along with your deposit check (made out to “Arthur Morris.”) You can also leave your deposit with a credit card by calling the office at 863-692-0906. If you register by phone, please print, complete and sign the form as noted above and either mail it to us or e-mail the scan. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me via e-mail.

|

|

|

Join Denise Ippolito and me for two great days of photography, fun, and learning at one of our soul places. We will surely be taking you out of the box on this workshop. Please click on the card to enjoy a larger version.

|

Bosque del Apache 2014 A Creative Adventure/BIRDS AS ART “Creative Photography Instructional Photo-Tour.” (IPT). NOV 24-25, 2014. 2-FULL DAYS: $729. Leaders: Denise Ippolito & Arthur Morris. Introductory Slide program: 7:00pm on Sunday 11/23.

Get Out of Your Box!

The Creative Bosque IPT is perfect for folks who want to learn to think outside the box, to create new and different images. This workshop is the perfect add-on for folks who are planning on attending the Festival of the Cranes. Learn to unleash your creative juices at the wondrous Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in San Antonio, New Mexico with two great leaders including the amazingly talented and creative Denise Ippolito. In-the-field instruction will include tips on gear set-up, on creating a variety of pleasing blurs, on getting the right exposure, and on designing pleasing images. And lots more. From vertical pan blurs to subject motion blurs to zoom blurs to multiple exposures we will cover it all. If conditions are perfect, we will not hesitate to take advantage of them to do some traditional bird photography. This workshop will include an inspirational introductory slide program on Sunday evening, 11/23, after dinner on your own, two morning and two afternoon photography sessions, all lunches, a digital workflow and Photoshop session after lunch on Monday, and an image critiquing session after lunch on Tuesday.

A $329 non-refundable deposit is required to hold your slot for this IPT. Your balance, payable only by check, will be due on 7/25/2014. If the trip fills, we will be glad to apply a credit applicable to a future IPT for the full amount less a $100 processing fee. If we do not receive your check for the balance on or before the due date we will try to fill your spot from the waiting list. If your spot is filled, you will lose your deposit. If not, you can secure your spot by paying your balance.

Please print, complete, and sign the form that is linked to here and shoot it to us along with your deposit check (made out to “Arthur Morris.”) You can also leave your deposit with a credit card by calling the office at 863-692-0906. If you register by phone, please print, complete and sign the form as noted above and either mail it to us or e-mail the scan. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact me via e-mail.

Bosque 2013 Kudos

From Brent Schoenfeld who attended with his friend Claudia, via e-mail:

You and Denise are an amazing team and it was a treasured experience to learn from and photograph with you both. You have gifted me a new ‘exposure’ discipline, which has catapulted me up to the level I’ve wanted to be at. I had seen the value before, largely from following your blog, and had started to embrace it, but with the workshop I find myself solidly and confidently established in a new and photographically more powerful place. Thank you for your blog, as well. It is a great learning tool. I hope to do more workshops with you two! Thanks for everything. Ciao for now, B.

From Gretchen Cole in an e-mail to the group:

Hello All, I finally have images ready to share. I am still thinking of the trip to Bosque and am so glad I could get signed on late and meet all of you. What a fun, energetic, and talented group. This was my very first trip to Bosque, and I know I will be back. It has grabbed me and I am already formulating a plan to return. This also was my very first bird photography experience and it was fantastic to have such good leaders willing to help and share their knowledge. Enjoy the holidays and I hope we meet again. Thanks again to Denise and Artie for sharing your knowledge without restraint 🙂 Gretchen

From Dave Klein via e-mail:

I wanted you to know that both you and Denise are icons in my photographic journey. What I liked about the workshop was the blending of styles you two represent: technical, compositional and creative. Your vast experience with Bosque told us when to be patient with a situation and let the photographic opportunity present itself and when to quickly move on to another when the circumstances weren’t in our favor. Thanks so much Artie for your dedication to your workshop participants and your readership. I feel privileged to say that I am both. Kind regards, Dave

From Sue Eberhart’s e-mail to the group:

Happy Day After Thanksgiving to all, The experience at Bosque, for me, was a once-in-a-lifetime journey. Before leaving home, I knew that it would be special trip but upon arrival and experiencing just a few minutes with all of you, I knew I was into something extraoidinary. The group’s passion and talent was infectious. As we know, the setting was so very special and the birds outdid themselves.

I am always looking for inspiration and I found all of you inspiring in many ways. Denise and Artie were always patient and willing to share their knowledge, techniques and skills. What more could one ask for? Snow? Yep, even that was arranged for and delivered. Attached are 5 of my best images. I can hardly wait to get home and begin to practice with our shorebirds but nothing will replicate the Bosque experience with all of you. Happy Holidays to you all and I hope we will meet again someday. Sue

From Carl Meisel via e-mail:

Thanks so much for allowing us to experience a once in a lifetime event. I had a great learning experience and am going home with myriads of keepers. I think we lucked out with the days we chose as we saw numerous blastoffs and beautiful sunsets. Thanks again. Carl–from the old Brooklyn neighborhood

Questions

Which card do you like best, the straight photography card (upper) or the creative card (lower)? Which is your very favorite image? Be sure to let us know why.

Light on the Earth

The original Fire-in-the-Mist image was featured as wrap-around cover art on the inspirational Light on the Earth, a large coffee table book that featured 30 years of the best images from the BBC Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition.

Great buy: Used Canon 800mm f/5/6L IS Lens for Sale

Friend and multiple IPT-veteran Monte Brown is offering his lightly used Canon 800mm f/5.6L IS lens in excellent condition for sale for $9,500. Purchase includes the lens case and hood, the 4th Generation Design Low Foot, the original foot, a LensCoat, the original invoice and the original Canon shipping carton. The lens was purchased new from B&H in April 2009 and was recently underwent a pre-sale clean and check by Canon. The buyer pays insured shipping via UPS Ground to US addresses only. The lens will be shipped only after your check clears.

The Canon EF 800mm f/5.6L IS USM Autofocus lens sells new for $13,223.00 so you will save a bundle on a great lens. No need to ever use a 2X…

If interested you can contact Monte by phone at 1-765-744-1421 or via e-mail.

Help Stop the Shooting of Snowy Owls at NY Area Airports

You might help stop the mindless shooting of Snowy Owls at Kennedy and other NY area airports by signing the petition here.

Last Year’s Grand Prize winning image by Lou Coetzer

Time is Running Out!

BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition

The December 31, 2013 closing deadline is fast approaching.

Learn more and enter the BIRDS AS ART 2nd International Bird Photography Competition here. Twenty-five great prizes including the $1000 Grand Prize and intense competition. Bring your best.

Support the BAA Blog. Support the BAA Bulletins: Shop B&H here!

We want and need to keep providing you with the latest free information, photography and Photoshop lessons, and all manner of related information. Show your appreciation by making your purchases immediately after clicking on any of our B&H or Amazon Affiliate links in this blog post. Remember, B&H ain’t just photography!

Amazon

Everyone buys something from Amazon, be it a big lens or deodorant. Support the blog by starting your search by clicking on the logo-link below. No purchase is too small to be appreciated; they all add up. Why make it a habit? Because I make it a habit of bringing you new images and information on an almost daily basis.

Typos

In all blog posts and Bulletins feel free to e-mail or leave a comment regarding any typos, wrong words, misspellings, omissions, or grammatical errors. Just be right. 🙂

IPT Info

Many of our great trips are filling up. You will learn more about how to make great images on a BAA IPT than anywhere else on the planet. Click here for the schedule and additional info.

December 11th, 2013

|

|

|

This tulip image was created at the Willem-Alexander Pavilion at Keukenhof, Lisse, Holland with the tripod-mounted Canon EF 600mm f/4L IS II USM lens and the Canon EOS 5D Mark III Digital camera body. ISO 400. Evaluative metering +2/3 stop: 1/5 sec. at f/16 in Manual mode.

Again, manual focus on the distal end of the pistil. Click on the image to enjoy a larger size.

Image #4: Tulip Multiple Exposure: “Beauty of Spryng”

|

How I Use Live View

I have found myself using Live View more recently than in previous years, especially for my flower photography.

Here is how and why I use Live View:

For flower or macro work, I often use Live View along with the 2-second timer to ensure sharp images in wind-free situations. Live View raises the mirror with the simple push of a button.

Again, mostly with flowers I have used Live View to ensure getting the right exposure by viewing the RGB histogram that you can bring up in Live View.

I use Live View when creating images with stacked teleconverters using Live Mode AF which focuses off contrast on the sensor. The funny thing is that once I have achieved focus I turn Live View off, look through the viewfinder, and push the shutter button to make the image.

I rarely use Live View at 10X magnification to focus manually with stacked teleconverters when there is not enough contrast for Live Mode AF to work.

And of course I use Live View to create the few videos that I make.

That’s about it. Note: I do not use Live View to check composition or image design. For that I make an image and then check the LCD on the back of the camera.

I never once thought that using Live View might in any way be potentially harmful to the sensor. Is there a danger? Keep reading.

|

|

|

This image was created in-camera at Keukehof Gardens in Lisse Holland on the first Tulip IPT with the tripod-mounted Canon EF 300mm f/2.8L IS II USM lens and the Canon EOS 5D Mark III.

ISO 100. Evaluative metering +1 stop at f/22 in Tv mode. What do you think was the shutter speed?

Central sensor Surround/AI Servo Rear Focus on the first row of pink tulips. Click here if you missed the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

|

How’d He Do Dat?

First off, do you like it? Do you hate it? Why? Be forewarned: I love it in part because of the outline effect on the pink tulips. Do let us know how you think this image was created in-camera? What technique or techniques were used? Please be as specific as you can. What was the shutter speed? Here is a clue: the original was rendered as a JPEG. Sometimes you can come up with something new and creative just by screwing around and having some fun.

|

|

|

This image was created at the Willem-Alexander Pavilion at Keukenhof, Lisse, Holland with the tripod-mounted Canon Telephoto EF 180mm f/3.5L Macro USM Autofocus lens and the and the Canon EOS-5D Mark III. ISO 800. Evaluative metering +2/3 stop: 1/25 sec. at f/8 in Av mode.

Central sensor AI Servo/Rear Focus on the closest large tulip petal on the left and re-compose. Click here if you missed the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

Live View (for Mirror Lock) and 2-second timer were used to create a sharp image of this Tulipa “Washington Orange” at a very slow shutter speed.

|

Live View Caution/A Guest Blog Post by Tim Grey

From the December 11, 2013 edition of the “Ask Tim Grey eNewsletter.”

Today’s Question: In a recent podcast episode Tim and Renee spoke highly of shooting with live view, especially for close focus shallow DOF [depth of field] circumstances. I have tried it for this purpose too and it works well. The Canon 6D manual, however, cautions against continuous live view use for a long period as it can cause internal temperature rise that would cause image quality to deteriorate, and I have read elsewhere it could possibly even cause camera damage. So my question is, how long is a “long period”?

Tim’s Answer: This is a great question, which of course doesn’t have a clear and specific answer.

To begin with, there is no question that using the Live View feature of your digital SLR will cause some problems. On any camera, such continuous use of the image sensor will lead to a rather significant (and relatively quick) increase in heat, which leads to greater noise in any images you capture. Of course, the same is true for capturing a large number of images in a relatively short period of time, especially under hot conditions. By contrast, if you use the Live View (and thus the image sensor) sparingly, and the temperature is relatively cold, there will be less heat buildup and thus less noise in the images.

For cameras (such as digital SLRs) that feature a shutter mechanism, the Live View option can also be harmful to the shutter, leading to earlier-than-expected failure of the shutter. That is because the shutter must remain open the entire time you are using Live View, which among other things can stretch the springs used in the shutter assembly.

Of course, you could also argue that simply taking a picture damages your shutter, since a shutter has a limited life expectancy measured in a number of actuations. That, of course, would generally relate to the number of images captured, and most shutter mechanisms in today’s digital SLR cameras have a life expectancy measured in the hundreds of thousands of actuations, perhaps up to a maximum of around one million actuations.

In any event, I do recommend being somewhat judicious in the use of Live View. I certainly couldn’t cite a number in terms of how long you can use Live View before too much heat builds up or until you’ve actually done harm to the shutter mechanism. But the point is that while I love using Live View, I do try to minimize the use.

In other words, if I feel it will improve a given photo, I will absolutely use Live View. But I will also try to limit the amount of time I’m using Live View by working somewhat quickly, and also by being conscious of these issues and not turning on Live View until I’m ready to use it, and turning it off as soon as I’m done using it.

I wouldn’t go to extreme measures here, as in most cases the harm done will be relatively modest. But it is something worth keeping in mind, and it is worth developing good habits when it comes to the use of Live View.

My Question

Does anyone know if the same potential risks occur while doing video? Heck, at least it was cold at Bosque 🙂

Follow-up from Time Grey via E-mail

Yes, the same issues relate to the capture of video clips. I am addressing that question in an “Ask Tim Grey eNewsletter” next week, as a reader posed the same basic question earlier today.

Pixology Magazine

Get in-depth articles every month that will help you optimize every aspect of your photography, with my digital magazine, Pixology. Subscribe today by clicking here.

It seems that I get a copy of Tim’s eNewsletter in my personal Inbox most every day. The amazing thing is that I read almost every one of them and always learn something new. You can subscribe to the Ask Tim Grey eNewsletter by clicking here.

|

|

If you would like to learn to be a better, more creative tulip photographer consider joining us on the 2014 Tulip IPT.

|

Holland 2014 7 1/2-Day/8-Night: A Creative Adventure/BIRDS AS ART/Tulips & A Touch of Holland IPT. April 17-April 24, 2014: $4995 Limit: 12/Openings: 5

Act soon: this trip is now a go and is filling quickly.

Join Denise Ippolito, Flower Queen and the author of “Bloomin’ Ideas,” and Arthur Morris, Canon Explorer of Light Emeritus and one of the planet’s premier photographic educators for a great trip to Holland in mid-April 2014. Day 1 of the IPT will be April 17, 2014. We will have a short afternoon get-together and then our first photographic session at the justly-famed Keukenhof. Most days we will return to the hotel for lunch, image sharing and a break. On Day 8, April 24, we will enjoy both morning and afternoon photography sessions.

The primary subjects will be tulips and orchids at Keukenhof and the spectacularly amazing tulip, hyacinth, and daffodil bulb fields around Lisse. In addition we will spend one full day in Amsterdam. There will be optional visits the Van Gogh Museum in the morning and the Anne Frank House in the afternoon; there will be plenty of time for street photography as well. And some great food. On another day we will have a wonderful early dinner at Kinderdijk and then head out with our gear to photograph the windmills and possibly some birds for those who bring their longs lenses. We will spend an afternoon in the lovely Dutch town of Edam where we will do some street photography and enjoy a superb dinner. All lodging, ground transportation, entry fees, and meals (from dinner on Day 1 through dinner on Day 8) are included.

For those who will be bringing a big lens we will likely have an optional bird photography afternoon or two. If we get lucky, the big attraction should be gorgeous Purple Herons in flight at a breeding marsh. We would be photographing them from the roadside. And we might be able to find a few Great-crested Grebes at a location near Keukenhof.

You will learn to create tight abstracts, how to best use depth-of-field (or the lack thereof) to improve your flower photography, how to get the right exposure and make sharp images every time, how to see the shot, and how to choose the best perspective for a given situation. And you will of course learn to create a variety of pleasingly blurred flower images. If you bring a long lens, you will learn to use it effectively for flower photography. Denise’s two favorite flower lenses are the Canon 100mm macro and the Canon 24-105mm zoom. Mine are the Canon 180mm macro lens and the Canon 600mm f/4L IS II, both always on a tripod and both often used with extension tubes and/or the 1.4X teleconverters. Denise hand holds a great deal of the time. For flower field blurs denise uses the same lenses mentioned above. My favorite is the 70-200 often with a 1.4X TC but I use both the 24-105 and the 600 II as well. Both of us use and love the Canon EOS-5D Mark III for all of our flower photography. The in-camera HDR and Multiple Exposure features are a blast.

One of the great advantages of our trip is that we will be staying in a single, strategically located hotel that is quite excellent. Do note that all ground transfers to and from Schipol will be via hotel shuttle bus.

What’s included: Eight hotel nights. All ground transportation except for airport transfers as noted above. In-the-field instruction and small group image review and Photoshop sessions. All meals from dinner on Day 1 through dinner on Day 8. The hotel we are staying in often offers both lunch and dinner buffets. The food is excellent. Whenever you order off the menu be it at the hotel or at one of the several fine-dining spots that we will be enjoying at various locations, only the cost of your main course is included. On these occasions the cost of soups, appetizers, salads, sodas and other beverages, alcoholic drinks and wine, bottled water, and desserts are not included. This is done in part in hopes that folks will be less inclined to enjoy an eight course dinner so that we can get to bed early. As with all A Creative Adventure/BIRDS AS ART Instructional Photo-Tours both the photo sessions and the days are long. Nothing that we do however will be demanding. Being able to sit down on the ground with your gear is, however, a huge plus. Anyone in halfway decent shape should be fine.

Snacks, personal items, phone calls, etc. are not included.

Beware of seemingly longer, slightly less expensive tours that include travel days and days sitting in the hotel doing nothing as part of the tour. In addition, other similar trips have you changing hotels needlessly. The cost of this years trip is a bit higher than last years to reflect our increased experience and the extra hotel night that is included. One final note on other similar trips: the instructors on this trip actually instruct. On other similar trips the instructors, though usually imminently qualified, serve for the most part as van drivers….

Happy Campers only please. A non-refundable deposit of $1,000 per person is required to hold your spot. The second payment of $2,000 due by October 30, 2013. The balance is due on January 15, 2014. Payments in full are of course welcome at any time. All payments including the deposit must be made by check made out to “Arthur Morris.” As life has a way of throwing an occasional curve ball our way, you are urged to purchase travel insurance within 15 days of our cashing your check. I use and recommend Travel Insurance Services. All payments are non-refundable unless the trip fills to capacity. In that case, all payments but your deposit will be refunded.

All checks should be made out to “Arthur Morris” and sent to: Arthur Morris, PO Box 7245, Indian Lake Estates, FL 33855. Please fill out the paperwork here and include a signed copy with your deposit check.

For couples or friends signing up at the same time for the tulip trip, a $200/person discount will be applied to the final payment.

Click here for complete details and lots of wonderful images with our legendary educational captions. Click here and see item one for lots more tulip images.

December 10th, 2013

|

|

This image was created on the Tanzania Summer Safari with the Canon EF 24-105mm f/4L IS USM lens (hand held at 65mm) and the Canon EOS-1D X. ISO 400. Evaluative metering +1/3 stop: 1/320 sec. at f/16 in Av mode.

Central sensor AI Servo Surround Rear Focus AF on the bird and re-compose. Click here if you missed the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

|

The 24-105

As regular readers know, I never leave home without my Canon EF 24-105mm f/4L IS USM lens. It comes in handy for a great variety of images; see “A Fitting Ending/Short Zoom Lens Tips” here to learn more about this useful B-roll lens. Whenever I head afield without my 24-105 it is usually not long before I am wishing that I had brought it along….

The bird in the tree is a Striped Kingfisher.

|

|

This image was also created from the top of our safari van on the Tanzania Summer Safari last August with the Canon EF 200-400mm f/4L IS USM Lens with Internal 1.4x Extender (with the internal TC in place at 345mm) and the Canon EOS-1D X. ISO 400. Evaluative metering +1/3 stop as framed in Av Mode: 1/320 sec. at f/16.

Central sensor/AI Servo/Surround–Rear Focus AF on the bird and re-compose. Click here to see the latest version of the Rear Focus Tutorial. Click on the image to see a larger version.

|

Going Wide with the 200-400 with Internal TC

To create the second story telling image in this series I went with the 200-400 at 345mm. Many folks would ask, “Why did you need the teleconverter in place?” I didn’t. It was in place to give me additional reach if needed; as I zoomed to frame the image I simply pressed the shutter button once I was pleased with the composition.

Note that when creating vertical images of small-in-the-frame subjects that placing the subject near one of the corners is almost always the best way to go. Learn more about Advanced Composition and Image Design in The Art of Bird Photography II (ABP II: 916 pages, 900+ images on CD only).

The Power of Twelve Hundred Millimeters

To create the relatively large-in-the-frame vertical image above I went with the 600II/2X III combo. Though many state openly that it is not possible to create critically sharp images with a 2X teleconverter I do just that consistently. For quite a while I worked at f/8 or f/9 with this combination (f/8 is wide open) but more recently I have begun stopping down to f/10, f/11, or f/13 when possible. To learn to make sharp images at long effective focal lengths see “Advanced Sharpness Techniques in The Art of Bird Photography II (ABP II: 916 pages, 900+ images on CD only). For those who as I have done gone completely to full frame bodies learning to work successfully with a 2X TC is huge advantage for both bird and wildlife photography.

Also relevant and of interest to many would be “Big Lens Choices for Canon and Nikon–As I See Them….” here.

The Image Optimization

After converting the RAW file in Canon’s Digital Photo Professional (click here to learn how and why I use DPP) I dust-spotted the image, eliminated several extraneous branches with a series of Quick Masks as detailed in APTATS I and regular layer masks, moved the bird up and a bit back in the frame using techniques from APTATS II, lightened the mask using Tim Grey Dodge and Burn techniques, and ran a 50% layer of my NIK 50/50 preset on the bird and the perch only. All the rest as described in detail in our in Digital Basics File, an instructional PDF that is sent via e-mail. It includes my complete digital workflow, dozens of great Photoshop tips, several different ways to expand canvas, all of my time-saving Keyboard Shortcuts, Quick Masking, Layer Masking, and NIK Color Efex Pro basics, image clean-up techniques, Digital Eye Doctor, and tons more.

I do realize that but for too much room at the top that the wider framing in the original post has merit.

Image Questions

#1- Which of these images do you think that I created first? Why?

#2: Why only +1/3 stop for all three of these images?

#3: Which is your favorite image? Why?

2014 Tanzania Summer Safari

If you are interested in joining us in Tanzania next summer please shoot me an e-mail and I will be glad to forward you the PDF with dates, itinerary, and price. With Jean-Luc Vaillant already signed up, this trip is a go.

Coming Soon

Stay tuned for next year’s Bosque IPT dates with the promised reduced rates and info on the Bosque Site Guide Current Conditions Update. The latter, which should be available be the end of this week, will be sent at no charge to all who have purchased the invaluable Bosque Site Guide. It will also be available as a separate purchase.

Also in the pipeline is a brand new MP-4 Photoshop Tutorial Video on creating high quality animated GIF files and using the Text Tool to type on images. It will sell for $4 and will be the first of many new MP-4 videos. See here for the current library.

December 9th, 2013

Jumping for Joy

Beautiful early morning light. The bird is pretty much right down sun angle and the exposure is spot-on. The subject is gorgeous. The wing position is perfect. There is a great look at the silver primary coverts contrasting with the black primaries and secondaries. The perfect image design that features the goose perfectly positioned against a distant, pleasingly de-focused mountain background. When I saw this image on the camera’s rear LCD screen I jumped for joy, though not very high out of concern for my healing left knee.

(Note: click here for the best diagram of dorsal wing surface feather tracts that I have seen.)

Yet the subject is not in sharp focus; the image is a total failure. I did not delete only because I knew that it would be perfect to make the point that in nature photography you need to do everything right. Often within a second or two at most…. That is the great challenge of bird and wildlife photography that drives me to succeed.

|

|

|

This is a 100% crop of the goose’s head.

|

Near Perfection Equals Total Failure

As you can see plainly above, the bird’s eye and face are not sharp. The image is a total failure. As you will see immediately below, this failure was caused by operator error.

|

|

|

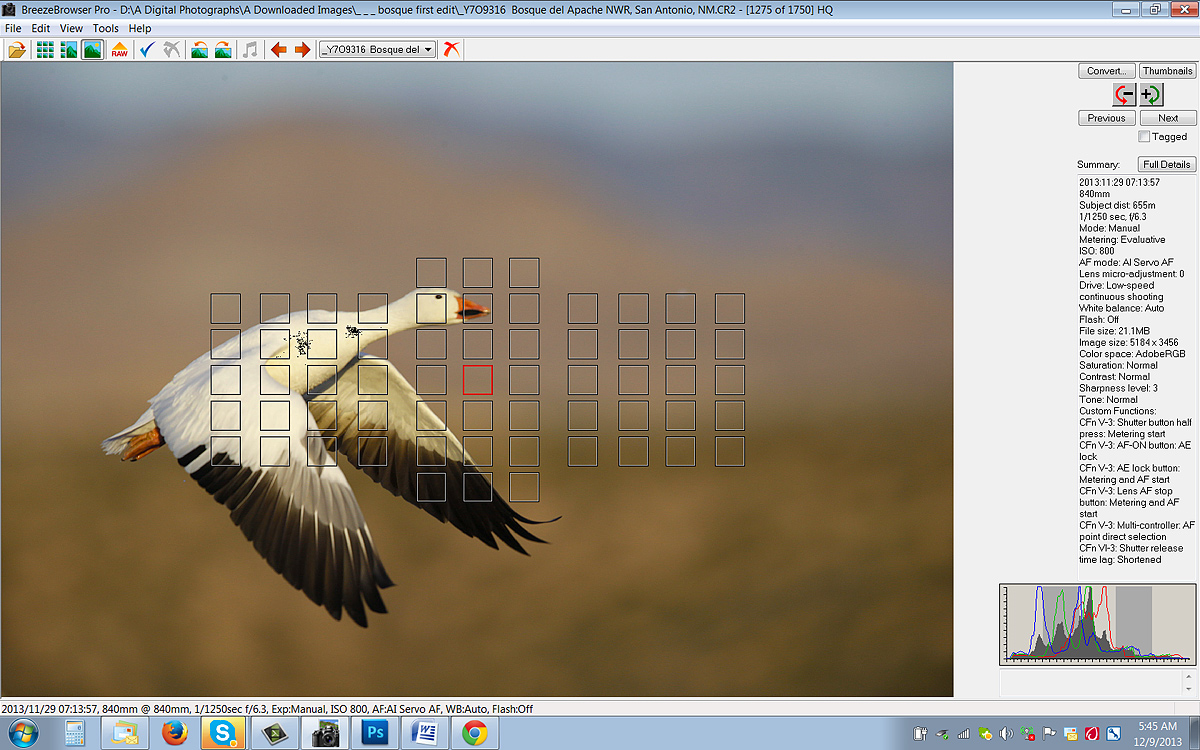

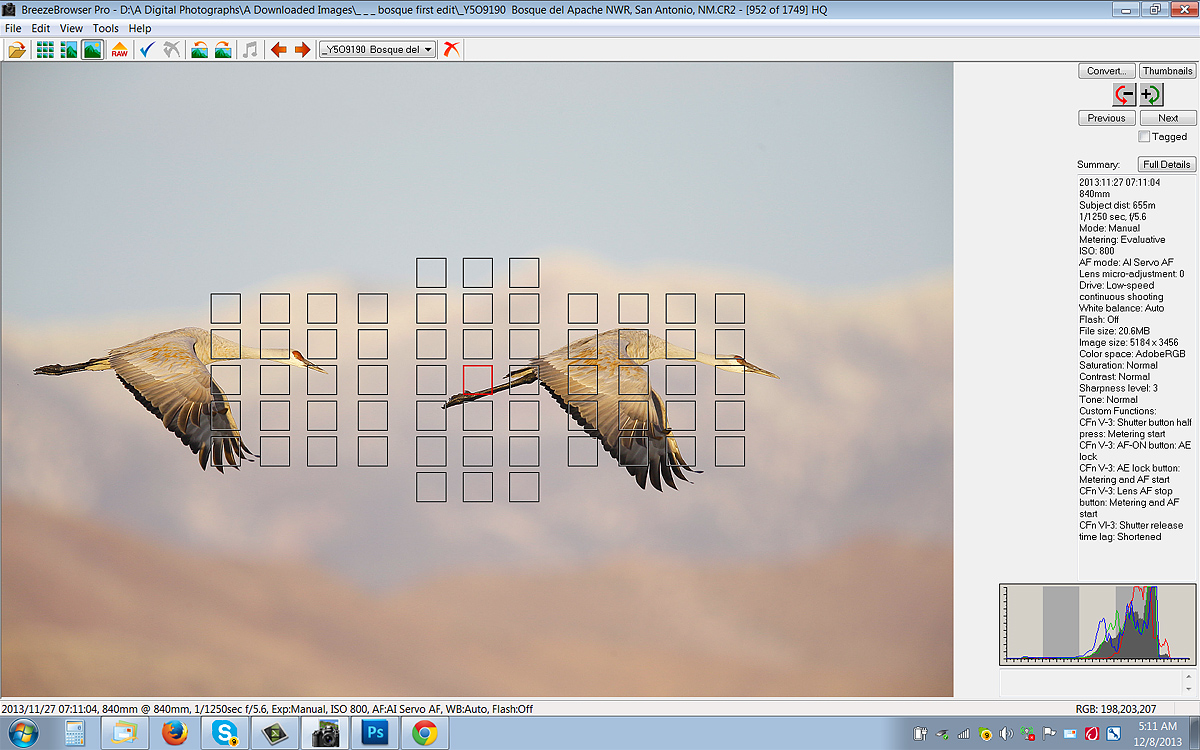

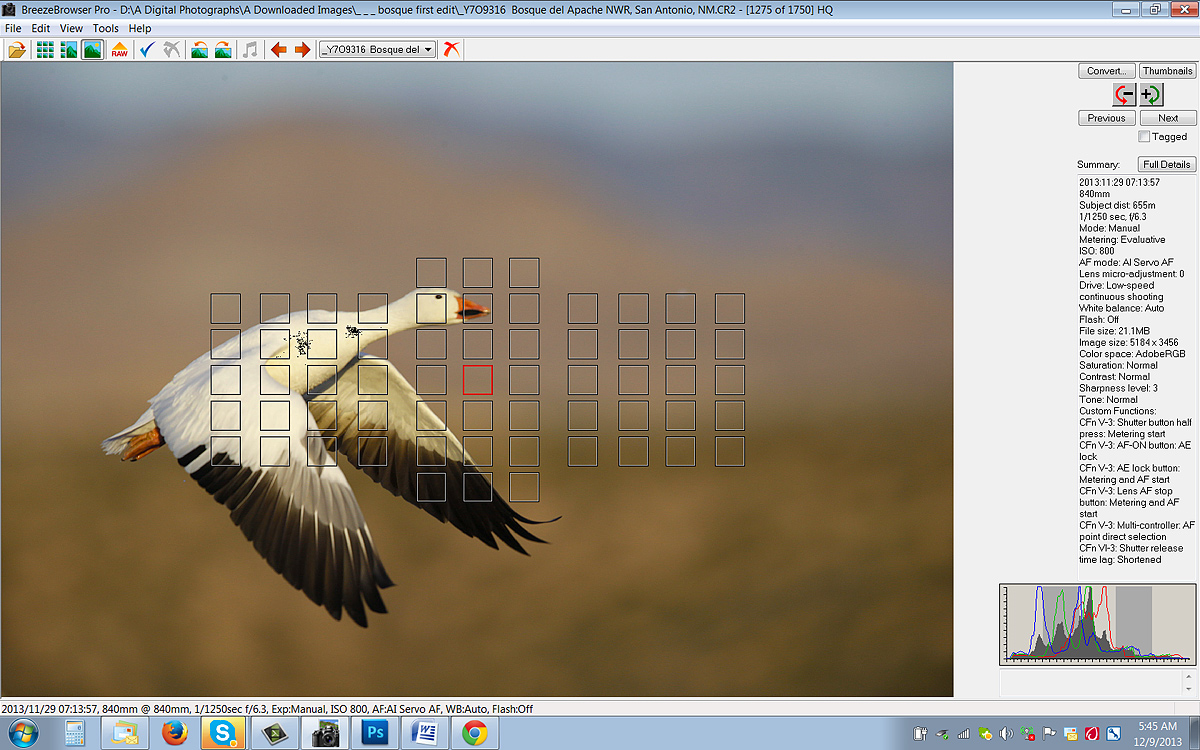

This is the BreezeBrowser Main View screen capture.

|

BreezeBrowser Main View Screen Capture

Above is the BreezeBrowser Main View screen capture for today’s image. Note that the illuminated red square shows that the center focusing sensor was active at the moment of exposure. But it was not on the subject…. In an ideal world one of the Surround AF points would have caught the top of the bird’s far wing. But the main problem was that I had never properly acquired focus and was not matching the speed of the bird in flight with my panning speed. Had I done my job properly the 1D X would have nailed accurate focus as it does so often and well.

Note: in Breezebrowser you need to check “Show Focus Points” under View to activate this feature. To see the focus points in DPP check “AF Point” under View or hit Alt L. Hit Alt M to see Highlight Alert. To learn how and why I use DPP (Canon Digital Photo Professional) to convert my RAW files, see the info on our DPP RAW Conversion Guide here.

Note the perfect histogram and the smattering of flashing highlights on the goose’s neck. The highlight alert in Breezebrowser is a bit more sensitive than the highlight alert on all Canon camera bodies so the few flashing highlights on the subject here let me know that I have made a perfect exposure with the brightest WHITE RGB values at about 238. Just as I like them.